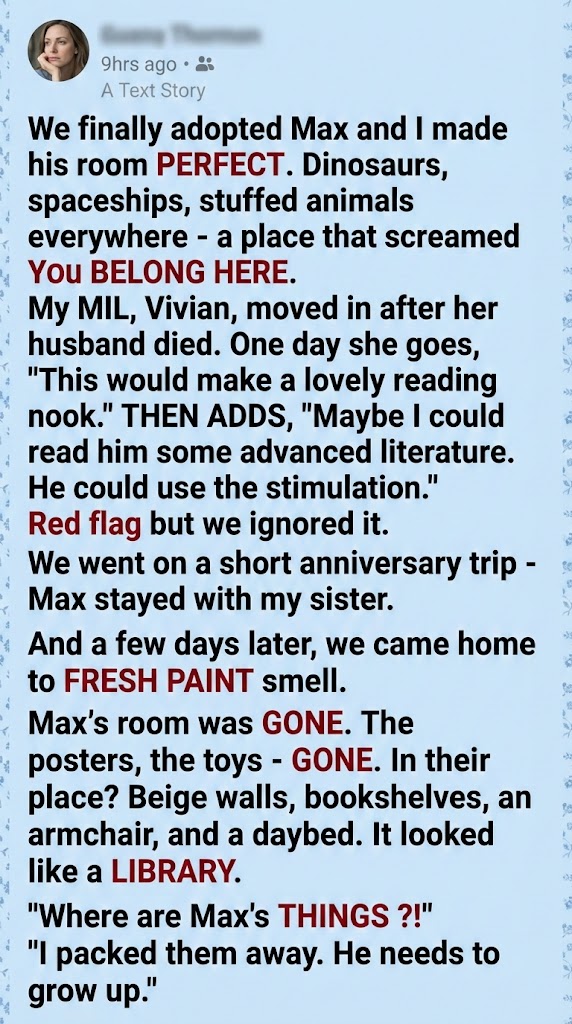

I saw red. The silence that followed her words was so thick it felt suffocating. “He needs to grow up?” I repeated, my voice barely a whisper, vibrating with fury. “Vivian, he is five. He has spent his entire short life feeling unwanted and temporary. That room wasn’t just toys; it was proof that this is his forever home.”

My husband, who had been standing in shocked silence in the doorway of the “library,” finally moved. He walked past his mother, not even looking at her, and went straight to the hallway closet. He flung the door open. Stacked inside were three industrial black garbage bags.

“You threw his life into trash bags,” he said, his voice dangerously low.

Vivian huffed, crossing her arms. “Don’t be dramatic. They are perfectly good storage bags. I was trying to elevate his environment. He needs intellectual stimulation if he’s going to catch up, not stuffed lizards.”

I brushed past her, ripping open the first bag. My heart broke seeing his glowing ceiling stars peeled off with bits of paint still stuck to them, jumbled in with his favorite spaceship quilt—the one I had sewn myself. It felt like a violation. It felt like she had tried to erase him the moment our backs were turned.

“Get out,” I said. I didn’t scream it. I just said it with absolute finality.

Vivian looked affronted. “Excuse me? This is my son’s house.”

My husband stepped next to me, putting a hand on my shoulder, presenting a unified front. “No, Mom. This is our family’s house. Max’s house. You crossed a line that you can’t uncross. You need to pack a bag and go stay at Aunt Sarah’s. Now.”

She tried to argue, tried to squeeze out crocodile tears about being an ignored widow trying to help, but we weren’t hearing it. While he ushered her out to her car, I started frantically dragging the beige armchair into the hallway.

We had two hours before my sister was dropping Max off.

It was a frenzy. We couldn’t fix the paint—the beige was still tacky and smelled sickeningly fresh—but we tore down the “advanced literature” bookshelves. We hauled his mattress back in from the garage where she’d stashed it. We didn’t have time to remount the posters properly, so we used blue painter’s tape to stick his dinosaurs and planets haphazardly over the drab walls. We dumped the toys out of the garbage bags onto the floor in a glorious, welcoming heap.

It didn’t look perfect anymore. It looked chaotic and patchy. But it smelled faintly of his bubblegum toothpaste instead of just paint fumes.

When the front door opened and we heard Max’s little footsteps, I felt sick with anxiety. What if he noticed the walls? What if he felt rejected again?

He walked to his doorway and stopped. He looked at the painter’s tape holding up his T-Rex poster. He looked at the pile of toys.

Then, he ran straight for his mattress and face-planted into his spaceship quilt, inhaling deeply. “My bed smelled like the garage,” he muffled into the fabric, then rolled over, grabbing his stuffed lizard. “But now my stuff is back.”

He didn’t notice the beige paint. He only noticed that his world had been returned to him.

I sat on the edge of the mattress and smoothed his hair, exhausted but relieved. Vivian was gone. The walls could be repainted bright blue tomorrow. But tonight, Max was safe, surrounded by the messy, childish proof that he belonged right here.